I am very happily in Valparaiso, Indiana for my step father’s 90th birthday party.

Karl Lutze was born in 1920 in Sheboygan, Wisconsin. As a boy he watched his father and his uncle pull up in the Automobile his father had ordered, picked up at the train station, read the operators manual and driven home. During WWII Karl studied to be a wartime pastor, but by the time he finished seminary school the war was over. Instead of going overseas, Karl was assigned to a poor black parish in Muskogee, Oklahoma. The rest of Karl’s life was cast at that moment.

Karl Lutze was born in 1920 in Sheboygan, Wisconsin. As a boy he watched his father and his uncle pull up in the Automobile his father had ordered, picked up at the train station, read the operators manual and driven home. During WWII Karl studied to be a wartime pastor, but by the time he finished seminary school the war was over. Instead of going overseas, Karl was assigned to a poor black parish in Muskogee, Oklahoma. The rest of Karl’s life was cast at that moment.

Happy Birthday, Karl. And thank you.

After bringing the church in Muskogee to vibrant and multicultural life – long before the topic of black/white American race relations became a popular cause – Karl was asked by the Lutheran diocese to help another church that had race relation problems. And another. And another.

One of the places he ended up at was an entirely white midwestern church which had received a letter from a black woman who wanted to join the congregation, but didn’t want to offend anyone by just showing up. Karl asked the pastor to call the board together and discuss it. A few of the members adamantly stated that they did not want to be part of a multi-racial church, and Karl let them know that it was OK for them to leave.

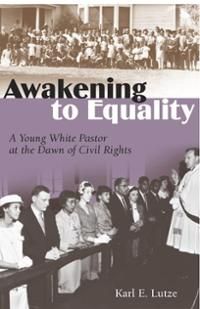

In 1963 Karl challenged the Christian press, asking why nothing had been written about race relations, and how could they call themselves Christians and remain silent at that time. They told him to write it himself, and To Mend the Broken was born (probably the best statement on topic I have ever read, though the terminology is out of date).

My mom was a student of Karl’s at Valparaiso University in the 1960s. At the time, Karl was organizing voter registration drives in the deep south, working with the Lutheran Human Relations Association – an offshoot of his early career – on a wide range of race relations from Native American issues to the more visible bichromatic prolems of the day, and deeply intertwined in many of the activities of the era. Decades later, after his wife Esther passed away and my parents divorced, Mom and Karl were married.

In the past fifteen years I have gotten to know Karl as well as anyone can. Karl does not talk about himself much, though he has so many stories that you can get him talking about where he was and put it together yourself. In his eighty-ninth year Karl still speaks, still writes, still does more for each community he touches than I am ever likely to do in total. The network of contacts represented by the Christmas Card distribution list Mom and Karl maintain reaches into the hundreds (I want to say it was 900 last year, but that sounds too high even though I saw the neatly sorted boxes with my own eyes, and that was a lot of paper…[update – the correct number is north of two thousand]). They visited us this past year in Raleigh, NC, and a friend of mine – the president of the Black Data Processing Association – joined us for dinner. I had told Rick some of Karl’s background and the two of them talked all night, after which Rick said, “You told me Karl was there but I didn’t know he was there! He knows everybody!”

You haven’t heard of Karl Lutze except from me, which is one of the minor tragedies and great glories of our time. Unlike others who have made a career out of being race relations figures, Karl has simply been doing the job. He was already doing the job when Martin Luther King Jr. first stood up to speak. He had been doing the job for a decade when Rosa Parks refused to move from her seat on the bus. Karl has been doing the job all along and you haven’t seen him doing it, which is the greatest measure of anyone’s success I can imagine.

I wrote this diary in 2008 on the anniversary of Bobby Kennedy’s death. That night while I wrote, Karl was sleeping. Tonight, as I write this, Karl sleeps again.

You have always earned the rest, Karl. Sleep well, and thanks for being so good to my Mom.

Thank you also, more than I can say, for being so good to all the rest of us, too.

Happy Birthday.

8 comments