We have all heard poignant stories about the many people across the country and around the world suffering from posttraumatic stress disorder. It can be a crippling condition, which can lead to a plethora of other problems, from generalized anxiety to depression to suicide. PTSD is a disorder affecting many Americans, and rates of PTSD have increased over the past several years due to US involvement in wars overseas. Many of our soldiers return home presenting with symptoms of this extraordinarily complicated and frequently debilitating disorder.

To gain a better understanding of what many Americans with this disorder – including many of our brave men and women in uniform – deal with on a daily basis, let us take a closer look at symptoms, causes, current research, and treatment options.

To gain a better understanding of what many Americans with this disorder – including many of our brave men and women in uniform – deal with on a daily basis, let us take a closer look at symptoms, causes, current research, and treatment options.

Posttraumatic stress disorder is categorized as an anxiety disorder characterized by three clusters of symptoms resulting from a traumatic event. Any type of trauma which involves a real or perceived threat to the life of an individual, or in any way severely damages the physical or emotional well-being of an individual – either through direct harm or the evocation of substantial fear – can result in the development of PTSD. Common causes include, but are by no means limited to: exposure to combat or torture; being a victim of kidnap, rape, robbery, assault, or domestic abuse; experiencing a natural or manmade disaster; bearing witness to a severe accident or injury; or receiving a life-threatening medical diagnosis.

Symptoms vary but typically follow a general pattern. Specifically, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual Fourth Edition (DSM-IV),

The essential feature of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder is the development of characteristic symptoms following exposure to an extreme traumatic stressor involving direct personal experience of an event that involves actual or threatened death or serious injury, or other threat to one’s physical integrity; or witnessing an event that involves death, injury, or a threat to the physical integrity of another person; or learning about unexpected or violent death, serious harm, or threat of death or injury experienced by a family member or other close associate (Criterion A1). The person’s response to the event must involve intense fear, helplessness, or horror (or in children, the response must involve disorganized or agitated behavior) (Criterion A2). The characteristic symptoms resulting from the exposure to the extreme trauma include persistent reexperiencing of the traumatic event (Criterion B), persistent avoidance of stimuli associated with the trauma and numbing of general responsiveness (Criterion C), and persistent symptoms of increased arousal (Criterion D). The full symptom picture must be present for more than 1 month (Criterion E), and the disturbance must cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning (Criterion F).

Though innumerable types of traumas can lead an individual to develop PTSD, the course of the disorder may be particularly severe or lengthy when it develops in response to certain traumas of “human design,” such as rape or torture. The symptoms of PTSD include a wide range of physical and emotional reactions, and the official diagnostic criteria are as follows:

309.81 DSM-IV Criteria for Posttraumatic Stress DisorderA. The person has been exposed to a traumatic event in which both of the following have been present:

(1) the person experienced, witnessed, or was confronted with an event or events that involved actual or threatened death or serious injury, or a threat to the physical integrity of self or others (2) the person’s response involved intense fear, helplessness, or horror. Note: In children, this may be expressed instead by disorganized or agitated behavior.

B. The traumatic event is persistently reexperienced in one (or more) of the following ways:

(1) recurrent and intrusive distressing recollections of the event, including images, thoughts, or perceptions. Note: In young children, repetitive play may occur in which themes or aspects of the trauma are expressed.

(2) recurrent distressing dreams of the event. Note: In children, there may be frightening dreams without recognizable content.

(3) acting or feeling as if the traumatic event were recurring (includes a sense of reliving the experience, illusions, hallucinations, and dissociative flashback episodes, including those that occur upon awakening or when intoxicated). Note: In young children, trauma-specific reenactment may occur.

(4) intense psychological distress at exposure to internal or external cues that symbolize or resemble an aspect of the traumatic event.

(5) physiological reactivity on exposure to internal or external cues that symbolize or resemble an aspect of the traumatic event.

C. Persistent avoidance of stimuli associated with the trauma and numbing of general responsiveness (not present before the trauma), as indicated by three (or more) of the following:

(1) efforts to avoid thoughts, feelings, or conversations associated with the trauma

(2) efforts to avoid activities, places, or people that arouse recollections of the trauma

(3) inability to recall an important aspect of the trauma

(4) markedly diminished interest or participation in significant activities

(5) feeling of detachment or estrangement from others

(6) restricted range of affect (e.g., unable to have loving feelings)

(7) sense of a foreshortened future (e.g., does not expect to have a career, marriage, children, or a normal life span)

D. Persistent symptoms of increased arousal (not present before the trauma), as indicated by two (or more) of the following:

(1) difficulty falling or staying asleep

(2) irritability or outbursts of anger

(3) difficulty concentrating

(4) hypervigilance

(5) exaggerated startle responseE. Duration of the disturbance (symptoms in Criteria B, C, and D) is more than one month.

F. The disturbance causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

Specify if:

Acute: if duration of symptoms is less than 3 months

Chronic: if duration of symptoms is 3 months or moreSpecify if:

With Delayed Onset: if onset of symptoms is at least 6 months after the stressor

Individuals differ in which symptoms are most prominently manifested, and a number of studies have been conducted on symptom expression. Some of these symptoms are considered more uniquely characteristic of PTSD than others. In the interest of more accurately diagnosing trauma victims, researchers Marshall, Schell, and Miles in 2010 examined and analyzed the symptoms of 294 survivors of communi

Individuals differ in which symptoms are most prominently manifested, and a number of studies have been conducted on symptom expression. Some of these symptoms are considered more uniquely characteristic of PTSD than others. In the interest of more accurately diagnosing trauma victims, researchers Marshall, Schell, and Miles in 2010 examined and analyzed the symptoms of 294 survivors of communi

ty violence and 234 wildfire evacuees. They suggest that eight of the 17 symptoms of PTSD represent dysphoria (general psychological discomfort) rather than features unique to cases of PTSD. Their findings indicate that while all symptoms of PTSD are indicative of dysphoria, hyperarousal may be the defining characteristic of PTSD (p. 133). “Hyperarousal” denotes a high degree of physical and psychological tension and typically includes insomnia, irritability/anger, a hyperactive startle response, and difficulty concentrating.

Immediately following any traumatic event, it is normal for an individual to experience emotional and physiological reactivity to reminders of it, but these responses usually lessen as time passes. A diagnosis of PTSD is not made unless it is determined that the symptoms an individual is experiencing are prolonged, pathological, and clinically significant. Innumerable factors – from the severity of the trauma endured to specific personality characteristics of the individual experiencing it – go into determining whether someone will develop PTSD in response to a traumatic event. In addition to long term emotional reactivity, immediate physiological reactions, such as dramatically increased heart rate, may be associated with greater risk for the development of the disorder. According to Pineles and associates, “increased heart rate measured shortly after a traumatic event is associated with increased risk for PTSD (Yehuda, McFarlane, & Shalev, 1998). Further, increased heart rate reactivity to trauma reminders is associated with greater maintenance of PTSD symptoms over time (Blanchard et al., 1996)” (p. 240).

Scientists have found that women may be especially prone to developing PTSD due to the effects of a molecule called PACAP, which affects stress responses.

scientists led by Dr. Kerry Ressler from Emory University conducted a study of 64 traumatized patients – in this case civilian patients at Atlanta’s Grady Memorial Hospital, not combat veterans. The researchers focused on a particular hormone-like molecule called PACAP (pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide), which is known to affect response to stress on the cellular level. They found that patients who suffered from PTSD had higher levels of PACAP than patients without the psychiatric disorder. What’s more, the higher the patients’ blood levels of PACAP, the more severe their PTSD symptoms.

But when the researchers split the data by gender, they found that the association between PACAP and PTSD was significant only in women. So the scientists designed a follow-up study with 74 traumatized female patients at the same hospital.

[. . .]

Ressler and his team then looked at the genes that code for PACAP and its receptor, PAC1. They found that women with PTSD were not only more likely to have high levels of PACAP, but were also more likely to have a variation to a gene for PAC1 that also responds to estrogen. That variation – which increased PAC1 sensitivity to both estrogen and stress – was not found in the gene itself but instead in the epigenome. Such epigenetic changes are acquired over time, through environmental influences – suggesting that people who are not genetically hardwired to be vulnerable to PTSD may become vulnerable through experience.

Anxiety sensitivity may play a key role in who develops posttraumatic stress disorder, as well as its ultimate course. The diathesis-stress model of mental illness conjectures that symptoms of mental illness manifest at the point wherein an individual with a vulnerability (e.g., genetic predisposition) is exposed to stress. In other words, in many cases it is believed that it is not solely genetics or environmental factors which lead to the development of mental illness, but in fact a synergistic combination of the two. In this vein, anxiety sensitivity is thought to play an integral part in the development of PTSD. According to Marshall, Miles, and Stewart, “anxiety sensitivity is generally viewed as a traitlike constellation of interrelated physical, cognitive, and social fears stemming from misinterpretation of symptoms of anxiety” (p. 143). The researchers go on to explain the ways in which anxiety sensitivity may exacerbate reactions to trauma.

Anxiety sensitivity may accentuate posttraumatic stress reactions in at least two ways. Individuals with preexisting anxiety sensitivity may respond more extremely to a traumatic stressor, distressed not only by the event but also by their own reactions. In this way, fear of anxiety may promote sensitization to trauma, lowering the threshold for fear reactions to traumatic events and increasing the possibility that exposure to relatively insignificant stressors might subsequently provoke adverse posttraumatic reactions (Rosen & Schulkin, 1998). Second, a traumatic event may generate both anxiety sensitivity and posttraumatic distress, with anxiety sensitivity ultimately serving to amplify adverse reactions. In this instance, fear of anxiety might be instigated, for example, by the pairing of previously innocuous arousal sensations with aversive reactions in a manner consistent with a classical conditioning account of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) onset and maintenance (e.g., Keane, Zimering, & Caddell, 1985). . . . In each circumstance, posttraumatic distress-which is characterized by three symptom clusters reflecting (a) reexperiencing of the event (e.g., intrusive thoughts), (b) avoidance of reminders of the event and emotional numbing, and (c) hyper-arousal (e.g., exaggerated startle response) (American Psychiatric Association, 2000)-is heightened by anxiety sensitivity. (Marshall, Miles & Stewart, p. 143)

Their study finds that the reverse is also true. Once an individual experiences PTSD symptoms, he or she will probably face increasing sensitivity to anxiety in general, which indicates that the interrelationship between PTSD symptoms and anxiety sensitivity is animated and complementary. The full study is available to the public for free and is well worth reading for anyone who has an interest in the subject.

Their study finds that the reverse is also true. Once an individual experiences PTSD symptoms, he or she will probably face increasing sensitivity to anxiety in general, which indicates that the interrelationship between PTSD symptoms and anxiety sensitivity is animated and complementary. The full study is available to the public for free and is well worth reading for anyone who has an interest in the subject.

Coping styles may also play a role in determining the development and subsequent course of PTSD. While an approach coping style is considered adaptive, avoidant coping has long been believed to play an important role in the exacerbation and maintenance of PTSD symptoms. Avoidant coping may involve elements of denial and typically impedes the individual’s ability to process and work through a traumatic experience. By preventing trauma victims from acclimatizing and habituating to the traumatic memory, it may inhibit the mind’s ability to recover naturally.

. . .it is not surprising that avoidant coping is associated with PTSD symptom severity both concurrently (Bryant & Harvey, 1995) and longitudinally (Benotsch et al., 2000). Avoidance has been theorized to interfere with successful processing of the trauma memory, habituation of negative emotions associated with the trauma memory, and extinction of fear responses conditioned to internal or external trauma reminders (Foa & Rothbaum, 1998; Keane & Barlow, 2002). Thus, individuals who are relatively reliant on

avoidant coping may be particularly likely to exhibit a strong association between physiological reactivity to trauma reminders and PTSD symptom maintenance. Avoiding trauma memories or reminders may impede the natural recovery process that would allow for heightened arousal to decrease over time (Foa & Kozak, 1986). Avoidance may also reinforce PTSD symptoms by signaling the individual that the memories are in fact dangerous (Foa & Kozak, 1986). (Pineles et al., p. 241)

The hypothesis that an avoidant coping style interferes with natural recovery may only prove true, however, for individuals who are extremely reactive to external triggers which remind them of the trauma. For many of the other characteristic symptoms of PTSD, coping style may be less relevant.

Terror Management Theory (TMT) is an existential social psychology theory which suggests that, due to humans’ cognizance and apprehension of their inevitable mortality, they are motivated to diminish keen subconscious death-related anxiety by seeking meaning in life, due to the presumption that such anxiety would disturb normal everyday functioning if not suppressed and controlled. Thus, theoretically, all human behavior is, at its core, prompted by fear of impending death. Individual worldviews, interpersonal attachments, self-esteem, and a number of other personal beliefs and values all come together to create an anxiety “buffer,” keeping an individual from anxiety-provoking thoughts brought on by consciously dwelling on fears of death. In relation to PTSD, Chatard and associates noted that, “From this perspective, traumatic events have the potential to disrupt crucial elements of people’s worldviews, self-esteem, and interpersonal attachments, thus rendering them unable to protect themselves from anxiety” (p. 2). Close encounters with death or other traumatic events can affect the mind’s ability to cope with death-related anxiety.

. . .there is growing evidence from clinical and social psychological research that severe trauma can produce a disruption of the anxiety buffer system, resulting in an alteration of terror management defenses. In addition, this appears particularly likely among individuals who dissociate at the time of the traumatic event and who exhibit the most severe symptoms of PTSD. (Chatard et al., p. 3)

Cognitively oriented theories place substantial emphasis on the individual’s belief structure. Theoretically, each individual operates on the basis of preconceived notions about the self, others, and the universe. The pattern of thoughts and beliefs which encompasses an individual’s worldview and dictates much of our behavior is known as a schema. The individual begins forming schemas in childhood, and by adulthood much of his or her belief system is firmly in place. The following theories to note in brief are cognitively based.

From a social-cognitive perspective, in 1986 Mardi Horowitz posited a theory for the development of PTSD which emphasized a “completion tendency.” Horowitz’s theory is concerned with information processing and assumes that trauma is difficult to process and assimilate into an individual’s preexisting belief system. Thus, this completion tendency is, in fact,

. . .the psychological need for new, incompatible information to be integrated with existing beliefs. The completion tendency keeps the trauma information in active memory until the processing is complete and the event is resolved. Horowitz also theorized that there is a basic conflict between the need to resolve and reconcile the event into the person’s history, and the desire to avoid emotional pain. When the images of the event (flashbacks, nightmares, intrusive recollections), thoughts about the meanings of the trauma, and emotions associated with the trauma become overwhelming, psychological defense mechanisms take over, and the person exhibits numbing or avoidance. (Barlow, p. 69-70)

Therefore it may be the actual process of incorporating traumatic experiences into an individual’s existing schemas, which leads to the expression of many PTSD symptoms. Similarly,

Shattered assumptions theory (Janoff-Bulman, 1992) also focused on trauma’s insult to meaning systems. According to this theory, all individuals develop fundamental, yet unarticulated, assumptions about the world and themselves (i.e., worldviews) that allow for healthy human functioning. The most important assumptions that constitute worldviews in this formulation include beliefs in a just, benevolent, predictable world in which the individual possesses competence and worth. The primary function of the worldview is to provide the individual with meaning, self-esteem, and the illusion of invulnerability. According to this theory, when individuals experience an event that violates their worldview (i.e., traumatic material that cannot be easily integrated with previously held worldviews), they no longer perceive the world as benevolent and predictable or themselves as competent and invulnerable and thus experience PTSD symptoms. (Park, Mills, & Edmonson, p. 1)

Yet another important cognitive theory was posited by Foa, Steketee, and Rothbaum (1989), and focused on the concept of “fear networks.”

on earlier work by Lang (1979), Foa and her colleagues suggested that traumatic events are represented in memory differently than other types of events, with traumatic events represented as interconnections between nodes in an associative fear network with a low activation threshold and unusually strong response elements. According to this theory, traumatic events differ from other events in that they violate formerly held concepts of safety. This disruption in safety beliefs means that the fear networks are easily activated by a wide variety of environmental cues, including those related only tangentially to the actual event. This model was later elaborated as emotional processing theory (Foa & Riggs, 1993; Foa & Rothbaum, 1998) to include broader information about the relationship between pre- and posttrauma worldviews and PTSD. In particular, emotional processing theory holds that individuals with rigid pretrauma belief systems are more vulnerable to PTSD than those with more flexible belief systems. That is, in the face of trauma, rigid positive beliefs about the self and world are more vulnerable to disruption, and rigid negative beliefs more vulnerable to confirmation. (Park, Mills, & Edmonson, p. 1-2)

Of interest is the language of the aforementioned theory, which specifically makes mention of “rigid” belief systems. Rigid, dogmatic schemas have long been associated with vulnerability to disruption. Inflexible belief systems leave little or no room for the incorporation of novel or unique information, and being presented with such information may create a sense of upheaval and disorientation.

One final theory is worth noting here. It deals not only with the effects of trauma on an individual’s meaning systems, but also with its effects on goal violation.

Park and her colleagues (Park, 2008; Park, Edmondson, Fenster, & Blank, 2008; Park & Folkman, 1997) extended the cognitive perspective in two important ways. First, they emphasized that individuals’ meaning systems comprise not only central beliefs or assumptions but also hierarchies of goals that structure and direct their lives. Therefore, although appraisals of belief violation have a potentially powerful impact on meaning systems, appraisals of the trauma as violating important life goals can also have a potent negative impact (Park, 2010). That is, when events are appraised as vio

lating what one wants or what one wants to have happen it can be highly distressing, regardless of whether that event is consistent with one’s beliefs. In fact, some research suggests that goal violation is more strongly related to distress than is belief violation (e.g., Park, 2008). This cognitive perspective, termed the meaning making model, also explicitly highlights the role of cognitive appraisals of discrepancies in affecting worldviews. That is, although many cognitive theories are based on a traumatic occurrence that is discrepant with preexisting meaning systems (e.g., Epstein, 1991; Janoff-Bulman, 1989; McCann & Pearlman, 1990), few have explicitly articulated the importance of understanding and directly assessing this discrepancy. (Park, Mills, & Edmonson, p. 2)

Interesting research has been conducted examining the link between PTSD and negative self-referential thought. In 2011 a group of researchers found that, relative to women without PTSD, women with PTSD held more negative opinions and beliefs about themselves. Women with PTSD were also found to experience more negative affect while viewing pictures of themselves. The type of trauma endured and severity of trauma exposure may have bearing on the affective content of thoughts of reference. Specifically, negative self-referential processing appears particularly striking in women who see the trauma as “directly impinging on the development and/or maintenance of adaptive self-representation, thereby causing significant shame and self-degradation (e.g., familial/partner emotional, physical or sexual abuse)” (Frewen et al, p. 1). Traumas involving rape or violent domestic abuse may have a greater tendency to lead to negative self-referential thought processes.

. . . women with PTSD endorsed more negative and less positive trait adjectives as self-descriptive, and experienced more negative and less positive affect in response to viewing pictures of themselves while listening to negative and positive trait adjectives. We find it interesting that endorsement of the self-descriptiveness of the trait adjectives also predicted affective responses during the VVSRP-Task. These findings corroborate experimentally an encounter commonly reported in clinical settings: Women with PTSD due to significant histories of interpersonal and/or familial maltreatment often experience negative thoughts about themselves, including while looking in mirrors. (Frewen et al, p. 7)

We have long known that the development of PTSD is often associated with subsequent interpersonal difficulties, and research in this vein involving troops’ relationships with romantic partners and family members upon their return home from deployment is extensive. Unfortunately, many of the people in need of help do not necessarily seek it out. In a 2010 study examining relationship adjustment and treatment utilization among National Guard soldiers returning from Iraq, Meis and colleagues noted that,

. . .early research suggests limited mental health service utilization among those in need. Among OEF/OIF soldiers screening positive for mental health problems, only 23 to 40 percent sought mental health care (Hoge et al., 2004). Among the cohort of National Guard soldiers from which the present sample was drawn, over 50% of those with probable PTSD or depression had yet to obtain mental health services 2-3 months following return from deployment (Kehle et al., 2010). (Meis et al., p. 561)

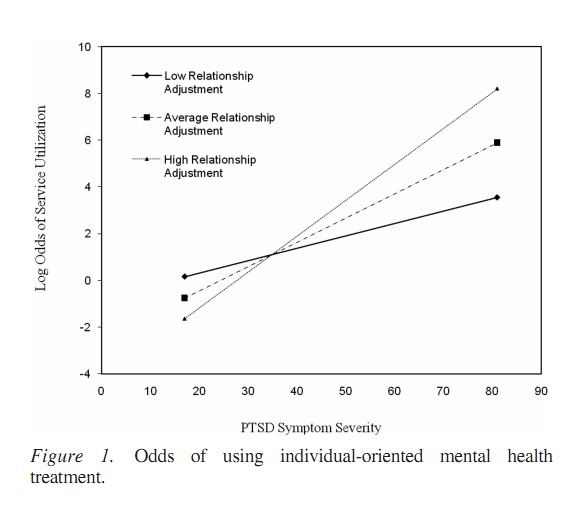

Meis and associates found a correlation between relationship adjustment and the chances of an individual manifesting PTSD symptoms seeking treatment.

A significant interaction was found, indicating that, as relationship adjustment improved, the association between PTSD symptom severity and odds of obtaining individual-oriented mental health services strengthened. While in the opposite direction of expectations, these findings are consistent with the notion that the support inherent in highly adjusted intimate relationships facilitates use of services for those with the greatest need for treatment (i,e., increasing severity of PTSD symptoms). . . .research also finds that intimate partners who report greater involvement with their significant others (i.e., veterans) are more likely to engage in veterans’ treatment for PTSD (Sautter et al., 2006). (Meis et al, p. 564)

Therefore, while it was expected that those with the most severe interpersonal difficulties might be more inclined to seek treatment, results of the study indicate that better relationship-adjustment actually increased the likelihood that an individual in need of treatment would seek it out. The researchers suggest that this pattern may be due to better communication between intimate partners, which may include dialogue on the importance of receiving mental health treatment. The image below depicts the study’s findings as related to symptom severity.

(Mies et al, p. 564)

PTSD comorbidity with substance abuse has long been cause for concern. There are several theories delineating the reasons this relationship may exist (the most intuitive of which may be self-medication theory), but they are beyond the scope of this diary. Statistics for substance use and abuse differ based on the age of the individuals and types of traumas experienced.

Individuals with PTSD are at higher risk for suicide than the general population. A recent military study shows a rise in suicide attempts and PTSD symptoms over the past few years.

“We’ve seen increases in suicide rates over the last several years,” said Robert Bray, the study’s senior program director. “I think this data is consistent with what we are seeing there.”

The 2008 Survey of Health Related Behaviors, released late Wednesday, was conducted by researchers with the Research Triangle Institute. It was last taken in 2005.

The percentage of servicemembers admitting to PTSD-like symptoms rose from 7 percent in 2005 to 11 percent in 2008. The largest jumps came from soldiers and Marines.

Soldiers who said they had PTSD-like symptoms rose from 9 percent to 13 percent, while Marines reporting such symptoms nearly doubled, from 8 percent to 15 percent.

“The stresses of repeated deployments are playing a part in the trends we are seeing,” said Jack Smith, acting deputy assistant secretary for clinical and program policy for the assistant secretary of defense for health affairs. “We’re working on the stigma aspect of this and there are more screening opportunities out there, so people are becoming more aware of this.”

I have written about military suicide before, and since then it appears that rates have only increased. PTSD increases the risk of suicide regardless of the type of trauma, and the lack of adequate treatment only exacerbates that risk. Unfortunately, many in need of treatment do not receive it. This may be due to lack of availability (although that is improving), or hesitance to seek treatment out

. A study by Wong and associates found that, of the trauma survivors surveyed and acknowledging a need for help,

66% reported thinking that their problem was not serious enough and 74% expressed wanting to solve problems on their own as reasons for not seeking treatment. Similarly, in a recent study of survivors of violence-related facial injuries, a majority of participants expressed an interest in receiving treatment for emotional problems related to the injury. However, they also reported experiencing a variety of barriers, including a belief that it is important to deal with problems by oneself and that such problems cannot be helped (Wong et al., 2007). (Wong et al., p. 2)

Despite the stigma associated with PTSD (and many other mental illnesses), the importance of seeking help is paramount, and there are many types of treatment recommended for use with sufferers of PTSD. Although spontaneous remission of the disorder is possible, it usually depends on the number and severity of traumatic events experienced (Kolassa et al., 2010). Generally speaking the benefits of treatment are worth the trouble of seeking it out and complying with medical advice. Many factors go into an individual’s choice to refuse or terminate treatment, however, and there are still numerous shortcomings in the field. More research is still needed in several areas, perhaps especially related to the development of better methods of treating diverse needs. In the military, minority groups may experience higher rates of PTSD than whites. This could be attributable to various factors, and it is especially worrisome because nonwhite patients may be more inclined to terminate treatment early. For example, one study found that, ” African Americans initially held more (pretreatment) positive attitudes toward mental health care. However, when African Americans did utilize care, they held more negative attitudes than Caucasians toward these services when assessed posttreatment and were less likely to return to use them (Diala et al., 2000)” (Lester, Resick, Young-Xu, & Artz, p. 481).

Despite the stigma associated with PTSD (and many other mental illnesses), the importance of seeking help is paramount, and there are many types of treatment recommended for use with sufferers of PTSD. Although spontaneous remission of the disorder is possible, it usually depends on the number and severity of traumatic events experienced (Kolassa et al., 2010). Generally speaking the benefits of treatment are worth the trouble of seeking it out and complying with medical advice. Many factors go into an individual’s choice to refuse or terminate treatment, however, and there are still numerous shortcomings in the field. More research is still needed in several areas, perhaps especially related to the development of better methods of treating diverse needs. In the military, minority groups may experience higher rates of PTSD than whites. This could be attributable to various factors, and it is especially worrisome because nonwhite patients may be more inclined to terminate treatment early. For example, one study found that, ” African Americans initially held more (pretreatment) positive attitudes toward mental health care. However, when African Americans did utilize care, they held more negative attitudes than Caucasians toward these services when assessed posttreatment and were less likely to return to use them (Diala et al., 2000)” (Lester, Resick, Young-Xu, & Artz, p. 481).

To mention just a few of the many types of treatment available for PTSD:

Exposure therapy is a popular form of treatment for PTSD. It aids individuals in coping with trauma-related thoughts and situations by teaching the patient breathing techniques, utilizing talk therapy to work through the trauma, and helping the patient approach situations that are related in some way to the trauma. Below is a video about exposure therapy released by the VA.

Cognitive therapies are also very popular today, and there are numerous ways in which they may be implemented. In cognitive or cognitive-behavioral therapies, much emphasis is placed on reframing thought processes. Patients are taught to understand the way they view the world – and the way they view the trauma(s) they have experienced – and restructure their thought processes. Variations on Albert Ellis’s rational emotive behavior therapy (REBT) and Aaron Beck’s cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) are common in clinical use. Research suggests these types of treatments can be effective. In a study conducted by Iverson and her colleagues, researchers found that the implementation of CBT with women who had experienced interpersonal violence actually reduced future risk for intimate partner violence.

. . .women who experienced reductions in PTSD and depressive symptoms over the course of treatment reported less IPV at a 6-month follow-up relative to women who did not respond to treatment, in terms of reductions in PTSD and depression symptoms. Women who experienced improvements in PTSD and depression were less likely to report IPV at the 6-month follow-up, even after controlling for the effects of being in a current relationship with recent IPV at the pretreatment assessment and the total number of lifetime sexual and physical interpersonal traumas experienced. (Iverson et al., p. 6)

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) is a heavily researched treatment option, which entails using eye movements to reduce the intensity of disturbing thoughts and stress reactions. Pioneered by Francine Shapiro, EMDR has been shown in several studies to in many cases significantly diminish distress related to traumatic memories. Some studies have suggested that it is more efficacious for the treatment of PTSD than both exposure therapy and CBT.

Medication may be useful for some sufferers of PTSD. Antidepressants, especially selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI’s), have been widely used to treat depressive symptoms in PTSD patients in recent years. Anxiolytics may be beneficial in treating some of the anxiety symptoms which accompany the disorder. Many other types of medication have been indicated in various cases. Here is a brief, useful chart listing several common types of medication used in the treatment of PTSD. Some more general information about medication is available here.

The methods listed above are but a few of the available treatments. New treatment options are emerging all the time. Last year several news studies were published on the use of animals, particularly dogs, in treating PTSD. For all the research we have on posttraumatic stress disorder – and there is, indeed, a world of research – new discoveries are still being made. We are still trying to understand this complicated disorder which diminishes quality of life for so many people around the world.

There is much yet to do.

Barlow, D. (2007). Clinical handbook of psychological disorders: a step-by-step treatment manual. USA: Guilford Press.

Chatard, A., Pyszczynski, T., Arndt, J., Selimbegovic, L., Dri Konan, P., & Van der Linden, M. (2011). Extent of trauma exposure and PTSD symptom severity as predictors of anxiety-buffer functioning. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 1(1), 1-10.

Frewen, P., Dozois, D., Neufeld, R., Densmore, M., Stevens, T., & Lanius, R. (2011). Self-referential processing in women with PTSD: affective and neural response. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1037/a0021264.

Iverson, K., Gradus, J., Resick, P., Suvak, M., Smith, K., & Monson, C. (2011). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for PTSD and depression symptoms reduces risk for future intimate partner

violence among inter

personal trauma survivors. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 1-10. Online First Publication. doi: 10.1037/a0022512.

Kolassa, I. Ertl, V., Eckart, C., Kolassa, S., Onyut, L., & Elbert, T. (2010). Spontaneous remission from PTSD depends on the number of traumatic event types experienced. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 2(3), 169-174.

Lester, K., Resick, P., Young-Xu, Y., & Artz, C. (2010). Impact of race on early treatment termination and outcomes in posttraumatic stress disorder treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(4), 480-489.

Marshall, G., Miles, J., & Stewart, S. (2010). Anxiety sensitivity and PTSD symptom severity are reciprocally related: evidence from a longitudinal study of physical trauma survivors. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 119(1), 143-150.

Marshall, G., Schell, T., & Miles, J. (2010). All PTSD symptoms are highly associated with general distress: ramifications for the dysphoria symptom cluster. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 119(1), 126-135.

Meis, L., Barry, R., Kehle, S., Erbes, C., & Polusny, M. (2010). Relationship adjustment, PTSD symptoms, and treatment utilization among coupled National Guard soldiers deployed to Iraq. Journal of Family Psychology, 24(5), 560-567.

Park, C., Mills, M., & Edmonson, D. (2010). PTSD as meaning violation: testing a cognitive worldview perspective. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 1-10. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1037/a0018792.

Pineles, S., Street, A., Mostoufi, S., Ready, C., Griffin, M., & Resick, P. (2011). Trauma reactivity, avoidant coping, and PTSD symptoms: A moderating relationship? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 120(1), 240-246.

Wong, E., Kennedy, D., Marshall, G., & Gaillot, S. (2010). Making sense of posttraumatic stress disorder: illness perceptions among traumatic injury survivors. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 1-10. Online First Publication. doi: 10.1037/a0020587.

12 comments