H ere is the final instalment of my talk to the Bond University Philosophical Society the other night. I must thank my hosts for a delightful evening.

ere is the final instalment of my talk to the Bond University Philosophical Society the other night. I must thank my hosts for a delightful evening.

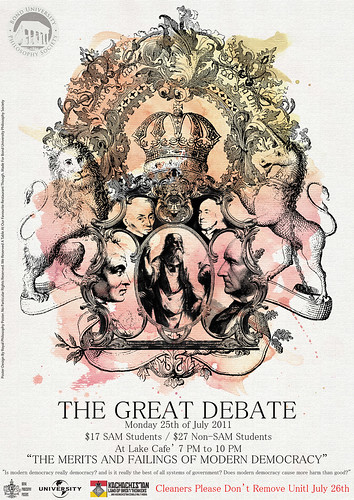

The subject was, “Is modern democracy really democracy?,” “Is democracy the best of all systems of government?” and “Does it do more harm than good?.” It seemed like a stacked deck to me at the time:

So here we are, at our dinner hour, considering if this political model, which has been shaped around our dramatic social evolution of nearly two modern centuries, is our best option. I think this can be dealt with quite simply with the droll but weighty observation of Winston Churchill:

“It has been said that democracy is the worst form of government except all the others that have been tried.”And we have tried many. It is hard to conceive how the alternatives, no matter how thoughtfully framed or benign, are not arguably some form of tyranny by modern standards, irrespective of legality.

So what are the merits of “democracy?”

Democracy has two essential virtues; that it is “just” in the sense of the “common good,” a justice that varies with the appropriateness of the contract and the wisdom and integrity of its executors. And also that it allows the majority the “arbitrary and reckless” opportunity to alter course, indeed reverse themselves, at some point in the future.

I can always tell when folks have been reading too much Plato.

The pitch for Winston’s argument:

No alternate system without these essential qualities would endure long among literate citizens, it seems. And it is hard to conceive of a political system that has these fundamental qualities which is not democracy in one of its myriad forms.

So much for “best of all systems of government” it follows that “modern democracy is democracy” without breaking stride:

Equally, on the basis of these two, shared essential qualities modern democracy is clearly democracy. The devil is in the detail; franchise, voting method, representation and scope of authority. There is a historical precedent for a wide variety of interpretations.Democracy as an abstraction is almost as intangible as capitalism and in many respects as ancient. In fact, it seems arguable that questioning the validity of modern democracy abstractly without engaging the specific terms of the arrangement is something akin to doubting capitalism out of frustration with an onerous contract from a mobile phone service provider. It will always require a negotiated settlement to resolve and it sometimes requires the consumer to take the initiative.

Our present system of democracy, like our body of law, is the hand we were dealt. And we may experiment with it freely within the constraints of Bismark’s maxim and the essential qualities discussed earlier.

Now the tricky bit:

Democracy is certainly not without inherent flaws, however. As Churchill also noted:

“The best argument against democracy is a five-minute conversation with the average voter.”And I’m guessing that was as credible in Cleon’s Athens as it is today, and it certainly raises an issue. Democracy rarely does harm for long because it relies on the principle that the electorate will act in its own interest. The degree to which this mechanism fails seems about the same as the degree to which a democratic system is perceived as broken.

The Athenian system was premised on much the same conditions as Plato recorded for Socratic dialogue; that both interlocutors are well informed and sincerely seeking “truth,” such as it is. If an electorate is polarized or agitated this can be a difficult hurdle to clear. In those circumstances significant harm is plausible, if not inevitable. The ancients were familiar with this as well.

It has been suggested that the contemporary influence of mass media has already undermined this principle, though one is inclined to argue that tabloid television and shock radio are not vastly different from the pamphleteering of the 17th and 18th centuries or the “yellow journalism” and radio demagoguery of the 20th. Recent newsworthy scandals, however, suggest that a corrosive influence may have emerged in the relationship between global corporate media and state actors. This could still be remedied via the ballot box if the political will existed to do so.

Since 9/11 we have also seen an erosion of our civil liberties, if that be harm, unthinkable in previous decades and with our overt or tacit consent. And collaterally our overreaction to the perceived threat of jihadist terrorism may yet inspire and embolden domestic extremists who seek to impose their minority views through public violence for which we have no immediate answer. This applies to emerging eliminationist rhetoric among the xenophobic and nativist Right in the United States and Europe as much as the recent horrifying events in Norway.

In fact the complacency of the electorate, concerned most with prosperity and least with the complexity of policy, creates uncertain prospects. In a world where some business and financial enterprises rival the resources of states, and far exceed their agility, management of national labour and treasury issues becomes problematic. The global economy is already out of the reach of many regulatory constraints traditionally imposed by states on behalf of their citizens. The impact of overseas labour on domestic employment without compensating, innovate industry is a genuine harm to many industrialized economies.

And the flinch in the clinch:

I have no idea how these ‘harms’ would be quantified against the base-load ‘good’ of the democratic system but I would argue that we are still well in the black, certainly over time. But this is not guaranteed by any measure.Broadly speaking, the current model of the electorate as solely revenue source and consumer in an entitlement society with a deregulating marketplace is arguably unsustainable, if only because it appears to have exposed the unleveraged, along with their limited assets, to the predations of the global economy.

The main architects of the global crash of 2008 were not states, although they had been persuaded to relax the regulatory environment in which it gestated; yet the states were obliged to cover costs from dwindling treasuries held in public trust. That income inequality was further exacerbated by asset losses from pension funds or superannuation accounts only further underlines the emerging risk to the current arrangements.

The view we are provided, from our lounge suites, of politics through the lens of infotainment, with elections presented almost as reality television, is probably also as much a risk to our democratic system as it is a commentary on the aesthetics of our popular culture. On the other hand Juvenal said much the same of imperial Rome:

“The people that once bestowed commands, consulships, legions, and all else, now concerns itself no more, and longs eagerly for just two things – bread and circuses!”Historically it has been up to the general population to engage with their government of the day to insure their ongoing best interests in a changing environment.

All right, so I ducked. And a final shot for the team:

As it appears that the structural threats to the present arrangement are not receding reawakening the political engagement of the public in the affairs of their local and federal government is an

attractive option and has been a viable political strategy.President Obama’s insurgent campaign stunned the political establishment by mobilizing and empowering a significant constituency of previously unengaged individuals and it was largely premised on the need for fundamental change. Whether that movement can be sustained in the ensuing fractious and overheated political environment or survive institutional resistance is yet to be demonstrated but is probably worth watching carefully.

Light applause.

4 comments