Stigma is a more complicated concept than one might initially guess upon mere casual consideration. Definitionally relatively simple, the causes, mechanisms, and consequences of social stigma are myriad and complex. You can find stigma, of one sort or another, most anywhere you look. Stigma will thrive in society wherever ignorance or fear or hatred of that which is “different” are acceptable mentalities. The tendency to stigmatize, label, and set certain groups/individuals apart from the rest of society as “other” is, to an extent, human nature. The need to categorize people, places, and things is normal — it’s just a function of how our brains work. We run into problems, however, when we begin allowing categories and labels to exclude and define people.

Personal experiences with stigma, in one or multiple forms, are common. One group most affected by social stigma is the mentally ill. The resulting effects are pervasive and painful.

It is an undisputed fact that individuals who experience mental health issues are often faced with discrimination that results from misconceptions of their illness. As a result, many people who would benefit from mental health services often do not seek treatment for fear that they will be viewed in a negative way. The World Health Organization agrees and says that in the 400 million people worldwide who are affected by mental illness, about twenty percent reach out for treatment. The World Psychiatry Association began an international program to fight the stigma and discrimination many people hold toward individuals who have mental health issues.

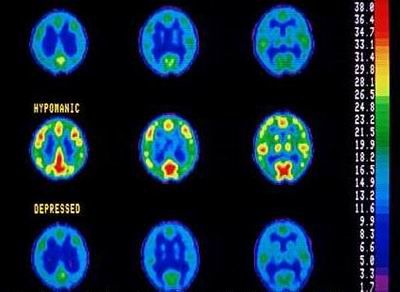

It is the 21st century, and though evidence-based research has shown us that mental illness is a real medical disorder, stigma is on the rise instead of on the decline. David Satcher, US Attorney General writes, “Stigma was expected to abate with increased knowledge of mental illness, but just the opposite occurred: stigma in some ways intensified over the past 40 years even though understanding improved. Knowledge of mental illness appears by itself insufficient to dispel stigma.”

There are plenty of theories about why stigma exists and how it works. Some have posited that there are 6 dimensions of stigma:

Concealability indicates how obvious or detectable the characteristic is to others. Concealability varies depending on the nature of the stigmatizing mark such that those who are able to conceal their condition (e.g., people with mental illness) often do so. Course indicates whether the stigmatizing condition is reversible over time, with irreversible conditions tending to elicit more negative attitudes from others. Disruptiveness indicates the extent to which a mark strains or obstructs interpersonal interactions. For example, interaction with people with mental illness is sometimes experienced as disruptive by others because of a fear of unexpected behavior by individuals with mental disorders. Aesthetics reflects what is attractive or pleasing to one’s perceptions; when related to stigma, this dimension concerns the extent to which a mark elicits an instinctive and affective reaction of disgust. Origin refers to how the condition came into being. In particular, perceived responsibility for the condition carries great influence in whether others will respond with unfavorable views and/or punishment toward the identified offender. The final dimension, peril, refers to feelings of danger or threat that the mark induces in others. Threat in this sense can either refer to a fear of actual physical danger (e.g., from a communicable disease such as leprosy) or exposure to uncomfortable feelings of vulnerability (e.g., uneasiness or guilt resulting from watching a disabled person negotiate a flight of stairs).

Using the above model, there are plenty of factors which affect the development, maintenance, and strength of stigma. And indeed, though the mentally ill are often stigmatized and discriminated against as a group, certain mental illnesses arouse more fear and antipathy in the minds of “healthy” individuals than others. Most people rightfully view individuals suffering with anxiety disorders as being quite distinct (in terms of symptoms, treatment, and prognosis) from those living with schizophrenia. There’s nothing wrong with recognizing very real differences, and dissimilar mental health problems shouldn’t be “lumped together” inappropriately. The problem arises when people assign unrealistically negative traits/characteristics to a group and separate them from “normal” people so completely that the stigmatized individuals are effectively stripped of their humanity in the eyes of the ignorant.

What are the origins of stigma really?

The affectively-driven approaches [to understanding stigma] share the assumption that prejudice originates as a negative emotional response. The root of the problem, according to this view, resides within human emotion. Negative stereotyping and discriminatory behavior are derived on the basis of this prior emotional root.

. . .

Cognitive appraisal theory suggests that emotional reactions to a person with mental illness are elicited by a prior process of cognitive apprasial (Arnold, 1960; Lazarus, 1984; Ortony, Clore, & Collins, 1988). This approach suggests that emotional reactions to a person with mental illness (e.g., “He makes me nervous.”) are determined by stereotype-based cognitive appraisals (e.g., “Because he’s mentally ill, he is dangerous.”).

. . .

According to the classical conditioning model, prejudice against a social group is shaped by socialization experiences that repeatedly pair an aversive stimulus with the social group.

The list of models, theories, etc. goes on and on. Understanding why stigma exists is essential in discovering effective ways to combat it. Regardless of which theory or hypothesis you might be inclined to support, I think most of us can agree that stigma is a very complicated, multifaceted problem. A problem which leads to… what?

Self-stigma makes people less likely to seek treatment.

. . .

Even medical students – who suffer from depression at high rates – report concerns about stigma. In a recent study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, 53.3 percent who reported high levels of depressive symptoms worried that disclosing their diagnosis would be risky.

Also, 34.1 percent of first- and second-year students and 22.9 percent of third- and fourth-year students reported that they’d feel less intelligent if they sought help. And these are the individuals who’d presumably be more comfortable than the average person in seeing a professional.

Self-stigma also can lead to isolation, lower self-esteem and a distorted self-image. “People with a mental illness with elevated self-stigma report low self-esteem and low self-image, and as a result they refrain from taking an active role in various areas of life, such as employment, housing and social life,” according to David Roe, professor and chair of the department of community mental health at the University of Haifa.

World of Psychology, When Mental Illness Stigma Turns Inward

Decreased self-esteem may not sound like a particularly devastati

ng consequence of stigmatization, but the anxiety, shame, and self-loathing that some mentally ill individuals experience can be profound. But it’s not just the mentally ill doing themselves harm by reacting poorly to society’s perceptions.

Societal stigma also can hamper treatment if people don’t receive the support they need from family and friends, she said, adding that all too often, people diagnosed with a mental illness find their loved ones acting differently toward them.

“It affects their network of support,” Gunter said. “If you were diagnosed with cancer or diabetes, you’d tell everyone and you’d be supported and prayed for and nurtured. If you tell people you have been diagnosed with a mental illness, you won’t necessarily receive that same level of support.”

Us News & World Report, Even Today, the Stigma of Mental Illness Won’t Fade

For those with mental illness the stigma experienced can result in a lack of funding for services, difficulty gaining employment, a mortgage or holiday insurance. Ultimately, feelings of stigma cause people to delay seeking help or even deny they have symptoms in the first place.

The Guardian, Crazy Talk: The language of mental illness stigma

So how do we approach it?

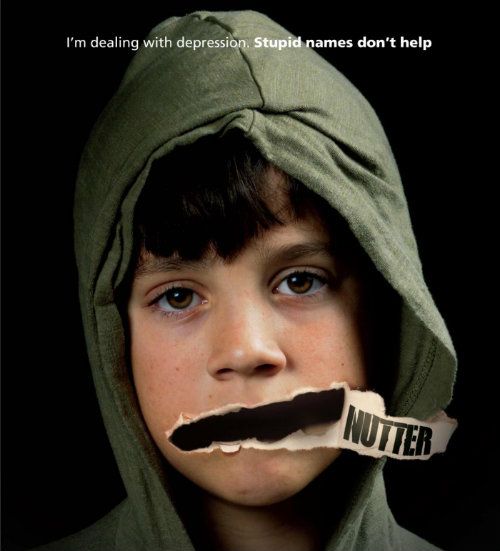

People have plenty of ideas about that too. Some tactics include educating others, becoming an advocate, eliminating derogatory words (e.g., “crazy,” “psycho”) from one’s vocabulary, encouraging and supporting the mentally ill in treatment, and reframing mental illness by calling it a “brain disease.” I’m sure you can all think of other things people could do to help fight stigma.

This Guardian article makes a strong case for weeding negative wording out of our vocabularies and eschewing the perpetuation of unpleasant characterizations of the mentally ill.

Casual language used to describe mental illness is decidedly negative. He or she is described as going mad, mental or psycho. Media portrayals reinforce this with images of violence and homicide associated with mental ill health. It was rare to see a discussion concerning the recent shootings in Aurora, Denver, without comments about the shooter’s mental health status.

Even children’s television seems to have gotten in on the act. One study in the British Journal of Psychiatry found that out of a sample of one week of children’s television, 59 out of 128 programmes contained one or more references to mental illness. Terms like “crazy”, “mad” and “losing your mind” were commonly used to denote losing control. Six characters were identified as being consistently portrayed as mentally ill. These characters were almost totally devoid of positive characteristics.

. . .

The sign “You don’t have to be crazy to work here but it helps” has become so common that it’s a cliché. People describing themselves as “a bit mad” usually mean that they’ve worn a sparkly hat at some point. Terms like mentalist, psycho, bonkers, insane and barking are thrown around like loose pennies in a conversational washing machine. Look at Terry, the mentalist. He’s bonkers. He’s so drunk he’s gone outside to punch the thunder for annoying the moon. Mad!

An argument could be made that these terms, while technically describing mental illness are not being used to specifically refer to mental illness. Rather they are referring to behaviour which they consider a little out of the ordinary. We can refer to this argument as Gervais’s Gambit. The problem is that if this language is making people with mental illness feel stigmatised, ashamed and isolated then the amount of thought behind it as it is used casually is largely irrelevant.

But it’s all easier said than done, and I say this as a person who would probably greatly benefit from a lot more doing and a little less saying. Many longtime moose may recall that I have what I suppose should be called “severe” mental health issues. I’m bipolar, and I’ve experienced and exhibited every symptom the doctors can think of. The symptoms I have struggled with and the effects of bipolar disorder on my life are manifold. In combating stigma, we walk a fine line. It is difficult to educate an uninformed person about mental illness in a way that will not create negative thoughts/associations, while still acknowledging and imparting the seriousness of mental illness and the detrimental effects it can have on sufferers’ lives. To paint a picture of mental illness as “not a big deal” or even as something which does not, to some degree, set the mentally ill apart from others… is to minimize and possibly even trivialize it. Varying disorders differ in their “severity” and their potential to impact the mentally ill individual and those around him/her, and even people with the “same” disorder will experience symptoms in different ways along a continuum. I do not discount the pain experienced by anyone due to mental illness, regardless of the diagnosis, but I will say that some disorders in particular are “serious business.”

But it’s all easier said than done, and I say this as a person who would probably greatly benefit from a lot more doing and a little less saying. Many longtime moose may recall that I have what I suppose should be called “severe” mental health issues. I’m bipolar, and I’ve experienced and exhibited every symptom the doctors can think of. The symptoms I have struggled with and the effects of bipolar disorder on my life are manifold. In combating stigma, we walk a fine line. It is difficult to educate an uninformed person about mental illness in a way that will not create negative thoughts/associations, while still acknowledging and imparting the seriousness of mental illness and the detrimental effects it can have on sufferers’ lives. To paint a picture of mental illness as “not a big deal” or even as something which does not, to some degree, set the mentally ill apart from others… is to minimize and possibly even trivialize it. Varying disorders differ in their “severity” and their potential to impact the mentally ill individual and those around him/her, and even people with the “same” disorder will experience symptoms in different ways along a continuum. I do not discount the pain experienced by anyone due to mental illness, regardless of the diagnosis, but I will say that some disorders in particular are “serious business.”

So how do I honestly educate people about someone such as myself without arousing unease, disgust, or fear in the people I am attempting to teach? Once the disorder manifested in me, I was not a decent person until a very brilliant psychiatrist finally got my medications right. I engaged in activities which were physically and emotionally perilous to myself and to others. My instability and volatility were plain for all to see, and it frightened even those who knew me well. I was inadvertently a danger to others, and I was very deliberately a danger to myself. Now, though? I’m a completely different person when medicated. (Still have plenty of problems, and I am certainly not asymptomatic, but life is better.) But how could someone tell my story, with or without explicit details, with any degree of truth and still expect empathy and understanding from the unenlightened?

I am not much of an advocate. I hide what I am at work, and I feel uncomfortable in situations where I fear my “secret” might be uncovered. I have tried to educate others while working in the counseling field, but I have done so purely from an academic standpoint. As a rule, I am not much of one to share my story “in real life,” even with the people who might most need to hear it. It has always unsettled me a little that I am, from a clinical diagnostic perspective, technically “sicker” than most of the clients and patients I have counseled. I fear that such knowledge would not inspire comfort or confidence in the people I work with.

I am not much of an advocate. I hide what I am at work, and I feel uncomfortable in situations where I fear my “secret” might be uncovered. I have tried to educate others while working in the counseling field, but I have done so purely from an academic standpoint. As a rule, I am not much of one to share my story “in real life,” even with the people who might most need to hear it. It has always unsettled me a little that I am, from a clinical diagnostic perspective, technically “sicker” than most of the clients and patients I have counseled. I fear that such knowledge would not inspire comfort or confidence in the people I work with.

I am also guilty of poor and insensitive word choices. I will say “crazy,” “nuts,” “psycho,” “lunatic,” and a plethora of similar terms quite readily. I actually do so far more in recent years than I did prior to my diagnosis. Early on, I clung very tightly to the “laugh or you’ll cry” way of thinking, and I learne

d to poke fun at myself (a behavior sometimes taken too far and coming across as disconcerting to loved ones). I laughed at the bipolar disorder because I sure as hell didn’t want to cry over it. I’m more balanced in my approach to it now, and I can accept it in ways that I couldn’t at first; however, I am still inclined to jokingly refer to myself as “nutty” or a “loon” or whatever else might come to mind. When admonished for it in the past, I’ve brushed it off by saying I’m trying to “take the word(s) back.” Which may or may not be true for me, depending on my mood (and lord knows I have a lot of those… see!).

I don’t really have any solutions. I thought I’d throw this out there because it’s been weighing heavily on my mind of late, in part due to all the negative talk about the mentally ill since Sandy Hook (by the way, if we could avoid turning this diary into a “gun control” rant/argument/whatever… it would be greatly appreciated).

So… any thoughts, anyone? Solutions?

Or if anyone would just like to take this opportunity to call me crazy, please feel free in the comments. 😉

[NOTE to Other Editors: Please do not FP due to personal content. Thank you.]

27 comments