Olaudah Equiano, c. 1745 – 31 March 1797

Most of us are familiar with the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave: Written by Himself. We know what a towering figure he was in the battle against slavery and for suffrage. I remember reading this as a child and relating his story to those of my ancestors who had been similarly enslaved.

I don’t remember being taught much-if anything-in school about other leading figures in the battle for abolition of that noxious scourge- chattel slavery-from the heart of Great Britain. Douglass joined the battle for abolition in about 1841, when

… he first heard Garrison speak at a meeting of the Bristol Anti-Slavery Society. At one of these meetings, Douglass was unexpectedly invited to speak.

After he told his story, he was encouraged to become an anti-slavery lecturer. Douglass was inspired by Garrison and later stated that “no face and form ever impressed me with such sentiments [of the hatred of slavery] as did those of William Lloyd Garrison.” Garrison was likewise impressed with Douglass and wrote of him in The Liberator. Several days later, Douglass delivered his first speech at the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society’s annual convention in Nantucket.

Before Frederick Douglass there were other black men and women who, alongside of whites had taken up the cause, from the heart of one of the European centers that was built on the back of those who died and toiled. That was in England.

One of the most powerful voices came from an African, portrayed above.

Olaudah Equiano (c.1745-1797): The Former Slave, Seaman & Writer

In his biography, he records he was born in what is now Nigeria, kidnapped and sold into slavery as a child. He then endured the middle passage on a slave ship bound for the New World. After a short period of time in Barbados, Equiano was shipped to Virginia and put to work weeding grass and gathering stones….

Equiano knew that one of the most powerful arguments against slavery was his own life story. He published his autobiography in 1789: The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano. It became a bestseller and was translated into many languages.

The book began with a petition addressed to Parliament and ended with his antislavery letter to the Queen. The tens of thousands of people who read Equiano’s book, or heard him speak, started to see slavery through the eyes of a former enslaved African. It was a very important book that made a vital contribution to the abolitionists’ cause.

To explore the early days and growth of the movement I suggest you take a tour of

The Abolition Project, where you will find a wealth of material, including teaching and learning tools. Their pages describe those beginnings.

What did a Quaker teacher, a Methodist preacher, a former slave, a former slaver, a ship’s doctor, a businessman, an African composer, a Baron, a scholar, an outspoken widow, a lawyer and a wealthy politician have in common? They were just some of the people who campaigned to bring about the abolition of the Transatlantic Slave Trade. For a long time, not many people in Britain knew and understood the evils of the Slave Trade. Those who did, and campaigned against it, faced abuse and occasionally even violence. They eventually formed a fellowship to abolish the trade.

The abolitionists also included many Africans who worked side by side with British abolitionists; they included Africans such as Olaudah Equiano, Quobna Ottobah Cugoano and Ignatius Sancho. They formed their own group ‘The Sons of Africa’, to campaign for abolition. As Reddie says, the ‘work of these African freedom fighters was important because it dispelled many of the misconceptions that white people held about Africans at the time’.It was not only freed slaves who fought against the trade. Enslaved people also fought for their freedom. You can read more about their struggle in the ‘resistance section‘. In Britain, the abolition movement gained in strength, despite setbacks and opposition from those who were making a great deal of money from the trade. The movement brought together a wide range of different people (black, white, male and female) and each had something unique to offer the cause.

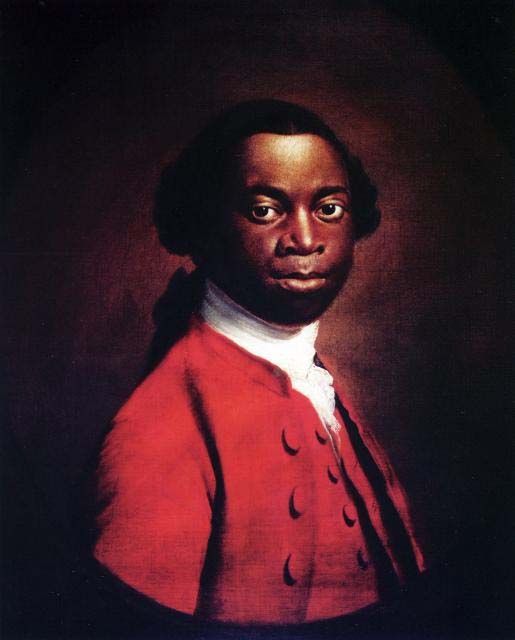

Ignatius Sancho, c. 1729 – 14 December 1780

Ignatius Sancho was a composer, actor and writer. He was a neighbour and friend of Ottobah Cugoano. Sancho was born in 1729 on a slave ship and spent the first two years of his life enslaved in Grenada. His mother died when he was very young and his father killed himself, rather than become enslaved. When he was two, his owner brought him to England.

He worked as a servant in Greenwich and then for the Duke of Montagu. Sancho taught himself to read and spoke out against the slave trade. He went on to compose music and write poetry and plays. In 1773, Sancho and his wife set up a grocer’s shop in Westminster. Sancho was very well known and his shop became a meeting place for some of the most famous writers, artists, actors and politicians of the day. As a financially-independent householder, he became the first black person of African origin to vote in parliamentary elections in Britain (1774 & 1780).

I teach a course on “Women in the Caribbean”, for our women’s studies program. One of the most important lives and voices we explore to examine the impact of slavery on women is the life and words of Mary Prince.

Mary Prince was born in 1788, to an enslaved family in Bermuda. She was sold to a number of brutal owners and suffered from terrible treatment. Prince ended up in Antigua belonging to the Wood family. in December 1826, she married Daniel James, a former slave who had bought his freedom and worked as a carpenter and cooper.

For this act, she was severely beaten by her master. In 1828, she travelled to England with her owners. She eventually ran away and found freedom, but only in England and she could not return to her husband. Mary campaigned against slavery, working alongside the Anti Slavery Society and taking employment with Thomas Pringle, an abolitionist writer and Secretary to the Anti-Slavery Society.

You can read the full text of her autobiography online. The History of Mary Prince, a West Indian Slave. Related by Herself. With a Supplement by the Editor.

She became the first woman to present a petition to Parliament, on 24 June 1829.

A Petition of Mary Prince or James, commonly called Molly Wood, was presented, and read; setting forth, That the Petitioner was born a Slave in the colony of Bermuda, and is now about forty years of age; That the Petitioner was sold some years go for the sum of 300 dollars to Mr John Wood, by whom the Petitioner was carried to Antigua, where she has since, until lately resided as a domestic slave on his establishment; that in December 1826, the Petitioner who is connected with the Moravian Congregation, was married in a Moravian Chapel at Spring Gardens, in the parish of Saint John’s, by the Moravian minister, Mr Ellesen, to a free Black of the name of Daniel James, who is a carpenter at Saint John’s, in Antigua, and also a member of the same congregation; that the Petitioner and the said Daniel James have lived together ever since as man and wife; that about ten months ago the Petitioner arrived in London, with her master and mistress, in the capacity of nurse to their child; that the Petitioner’s master has offered to send her back in his brig to the West Indies, to work in the yard; that the Petitioner expressed her desire to return to the West Indies, but not as a slave, and has entreated her master to sell her, her freedom on account of her services as a nurse to his child, but he has refused, and still does refuse; further stating the particulars of her case; and praying the House to take the same into their consideration, and to grant such relief as to them may, under the circumstances, appear right. Ordered, That the said Petition do lie upon the Table.

Her narrative is key, for hers is the only surviving voices we have documenting the horrors of enslavement in the Caribbean through the eyes of a woman.

Her description of work in the salt ponds is chilling.

Mary Prince had a number of different owners. One was the owner of saltponds.

I was immediately sent to work in the salt water with the rest of the slaves. I was given a half barrel and a shovel, and had to stand up to my knees in the water, from four o’clock in the morning till nine, when we were given some Indian corn boiled in water.

We were then called again to our tasks, and worked through the heat of the day; the sun flaming upon our heads like fire, and raising salt blisters in those parts which were not completely covered. Our feet and legs, from standing in the salt water for so many hours, soon became full of dreadful boils, which eat down in some cases to the bone.

We came home at twelve; ate our corn soup as fast as we could, and went back to our employment till dark at night. We slept in a long shed, divided into narrow slips. Boards fixed upon stakes driven into the ground, without mat or covering, were our only beds.”

Prince was key in inspiring women to become involved in anti-slavery activities. Though women did not have the vote, they could and did organize. Hearing Mary Prince speak wiped away any illusions about what happened to women on those far away plantations.

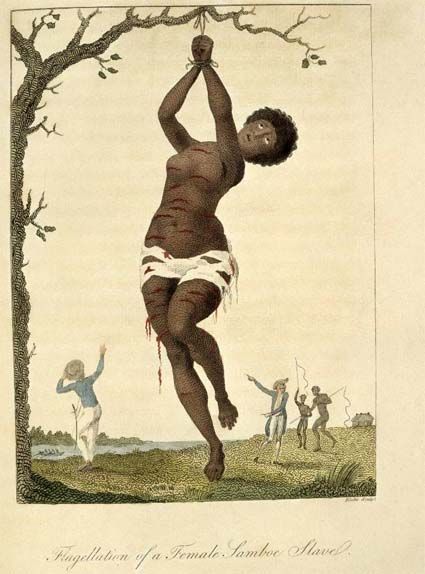

Capt. Stedman: “[the] first object which presented itself after my landing … a young female slave, whose only covering was a rag tied round her loins, which, like her skin, was lacerated in several places by the stroke of the whip. The crime which had been committed by this miserable victim of tyranny, was the nonperformance of a task which she was apparently unequal, for which she was sentenced to receive two hundred lashes, and to drag during some months, a chain several yards in length, one end of which was locked around her ancle, and the other was affixed a weight of at least a hundred pounds…”

I find that even today, students have no clear picture of the lives and deaths of enslaved women. The stereotypes of mammies and maids in the home, have no grounding in the reality of how many women did hard field labor. This print is used on the cover of Slave Women in Caribbean Society, 1650-1838, by Barbara Bush, another one of the texts we use in the class.

Women’s groups in Britain were key in organizing the boycott of slave grown sugar.

As the main food purchasers, women played an important role in organizing the sugar boycotts of the 1790s, after the bill for the abolition of the Slave Trade was defeated in Parliament in 1791. Over 300,000 people joined a boycott of sugar which had been grown on plantations that used the labour of enslaved people.

It is important to understand that the abolition movement had a powerful impact on other efforts for social change.

The abolitionists set in motion Britain’s first, mass social movement. Their rallying themes of liberty and equality influenced reforming campaigns for the right to vote, to form trades unions and the feminist movement. Their techniques of consumer boycotts and petitions are used to this day.

Lest you think the battle to portray this history has been won in England, activists were organizing to keep Mary Seacole (pioneering nurse and heroine of the Crimean War) and abolitionist Olaudah Equiano in the school curriculum.

Over 40 leading British trade unionists and personalities want the man in charge of schools to rethink his proposals to axe Crimean war heroine Mary Seacole and abolitionist Olaudah Equiano as required study in UK schools. In the open letter to the Education Secretary, the signatories told Michael Gove that it would be ‘historically and culturally incorrect to remove them’. Zita Holbourne, who has helped to organize the campaign, says their inclusion is for the benefit of everyone.Campaigners say they are worried what the removal of these two black figures say about British history. Should it be, they argue, male, pale and stale? In other words, a history of old, white men told with a particular bias in mind. In summer where British multiculturalism was celebrated with Jessica Ennis and Mo Farah having their achievements applauded there should be more figures of history, not fewer.

cross-posted from Black Kos

13 comments