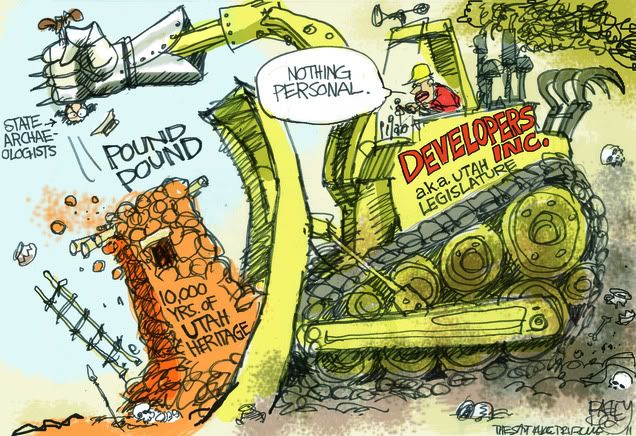

Recently, another battle in the war on science was lost when the State of Utah summarily fired nearly all of their state archaeologists to comply with ‘budget cuts’:

The Utah Department of Community and Culture on Tuesday laid off the state archaeologist and two assistants, leaving the Antiquities section with just two employees: those responsible for maintaining a database necessary for development of roads, railways, buildings and other projects.

Department acting Director Mike Hansen said he was simply carrying out budget cuts ordered by the Legislature to eliminate programs that receive state funds and that do not carry out requirements of state or federal law.

Coincidentally [!!], the firings come just as Utah legislators have ordered the Department of Community and Culture to ‘restructure’ or get this, eliminate itself. Wayne Harper, both a Republican State Representative and a developer, has introduced H.B. 287, a law that requires the agency to improve efficiency, reduce the cost of government, and “better focus the state and its employees.” Naturally, some wonder if the terminations are more politically motivated than driven by budgetary concerns.

For my part, I can’t help but wonder exactly what it is Rep. Harper thinks the state and its employees should better its ‘focus’ on?

State archaeologist Ronald Rood, who was among those dismissed, said in a professional association website post that Utah “showed its disdain for archaeology and Utah’s vast cultural heritage.” In a separate interview with The Tribune, he said that no other programs in the state Division of History had been cut and suggested there may have been a political motive behind the change: to eliminate employees who sought to protect archaeological sites threatened by development.

Rood, along with state archaeologist Kevin Jones and physical anthropologist Derinna Kopp, who also lost their jobs Tuesday, stepped into the view of Gov. Gary Herbert, lawmakers and the Utah Transit Authority in recent years when they raised concerns about a proposed commuter rail station planned in Draper. UTA proposed the train stop and mixed-use development on the footprint of an ancient American Indian village, the earliest known location of corn farming in the Great Basin.

“We always have tried to stand up for archaeology,” Rood said.

“We were pretty vocal over the issue of the [rail] station down in Draper that was going to be placed over a 3,000-year-old archaeological site.”

You bet they were vocal, and successfully so. As a result of their efforts (and those of Tribal and other conservation minded groups), the very significant archaeological site was finally spared destruction in the summer of 2009:

Gov. Gary Herbert signed a conservation easement with an environmental group Tuesday evening to protect ecologically and archaeologically significant land in Draper near 13500 South and the Jordan River in perpetuity.

That means a proposed FrontRunner south commuter-rail station will not be built on the 252 aces on which there are artifacts from a 3,000-year-old Native American village and a nesting place for migratory birds around the Great Salt Lake.

Ironically, the affected land was slated for protection by legislation passed way back in 2000, but the signing of an easement was delayed after Greg Curtis , the GOP House Speaker-turned-lobbyist approached State officials on behalf of a client who wanted to swap land in the area to facilitate development.

A scenic archaeological site that’s on track to become a transit-oriented development in Draper was all set for permanent preservation last summer until then-House Speaker Greg Curtis stepped in on behalf of a landowner he represented.

State lawmakers in 2000 set aside 252 acres by the Jordan River near 13500 South intending permanent protection of a buried 3,000-year-old American Indian village and open space linking to a burgeoning river parkway. The law they passed also directed the Department of Natural Resources to grant a perpetual conservation easement to a preservation group willing to manage the resulting parkland.

It took years to find that willing group, DNR Executive Director Mike Styler said Tuesday, but last summer the state was ready to sign an agreement with Utah Open Lands. That’s when Curtis contacted Styler and asked if he would hold off. Curtis, an attorney, represented a private landowner who wanted to trade adjacent land to get better access to nearby Bangerter Highway.

“He said, ‘I’m calling today not as Speaker Greg Curtis, but as attorney Greg Curtis‘” Styler recalled Tuesday.

[snip]

Curtis, who lost a re-election bid in the fall, now lobbies for Utah Transit Authority and on school issues for Draper City. When approached Tuesday at the Capitol for comment about his involvement, he initially refused.

“Go find another f—— boogeyman,” he said.

I don’t know, if the speaker of the House strong arms a state agency that depends largely on himself (and the Legislature he sets the agenda for) in an effort to, you know, assist a client, does that make one a ‘fucking boogeyman’? With a conflict of interest that white-hot, maybe ‘unethical assclown’ is a better characterization. But hey, the 252 acres of archaeological site are now legally protected and the proposed rail station and associated developments have been slated for an adjacent parcel of private land, so all’s well that ends well, right? Nope, not necessarily:

Relics and rails are colliding again, this time at 12800 South near an ancient American Indian ruin where the Utah Transit Authority plans a stop for its FrontRunner commuter line between Salt Lake City and Provo.

A political showdown is brewing between the city of Draper and a California developer on one side and Utah Indian tribes and environmentalists on the other. The Army Corps of Engineers, charged with protecting the country’s waterways, looks to be the referee in the tug of war.

At issue is 134 acres of private land that is slated for a multi-use development just south of the proposed FrontRunner station at 12800 South. That privately held land is also adjacent to 252 acres of state land near the Jordan River where archaeologists found evidence of an American Indian village dating back 3,000 years.

But according to state archaeologist Kevin Jones, the antiquities on the state land extend onto the adjacent private property.

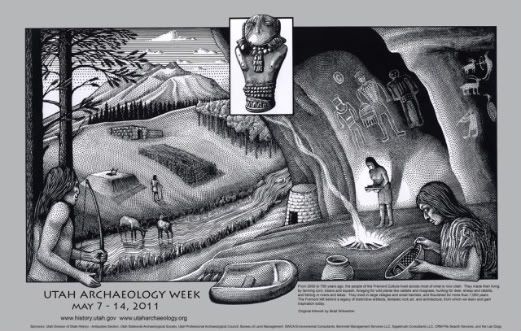

As part of the state Historic Preservation office, Kevin Jones was part of the team responsible for reviewing the assessment of impacts to archaeological sites in area of proposed development in compliance with laws like the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 (NHPA) and the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), and cataloging human remains found on state and private lands for repatriation to American Indian tribes in accordance with state and federal laws like the U.S. Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990 (NAGPRA). These folks also conducted annual educational outreach programs in Uta

h’s public schools during an Archaeology Week that included field trips and lecturers.

When they were told to vacate their offices this last Tuesday morning, the three archaeologists left behind unfinished written reports and forensic evaluations for about 100 sets of skeletal remains, three of which were still under analysis in the lab. All that aside, there are obviously still issues to consider with regard to the proposed rail station. Though the project has been moved to nearby private land, the Utah Transit Authority still needs to obtain an amendment to the 2008 permit issued by the United States Army Corps of Engineers under section 404 of the Clean Water Act. The issuance of an amended permit may trigger a Federal nexus that requires the Army Corps to comply with Section 106 of the NHPA, which states:

Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 (NHPA) requires Federal agencies to take into account the effects of their undertakings on historic properties, and afford the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation a reasonable opportunity to comment. The historic preservation review process mandated by Section 106 is outlined in regulations issued by ACHP.

[snip]

The responsible Federal agency first determines whether it has an undertaking that is a type of activity that could affect historic properties. Historic properties are properties that are included in the National Register of Historic Places or that meet the criteria for the National Register. If so, it must identify the appropriate State Historic Preservation Officer/Tribal Historic Preservation Officer * (SHPO/THPO*) to consult with during the process.

See, Kevin Jones and his colleagues, as part of the State Historic Preservation Office, may have had some influence in this debate — if they hadn’t just been fired from a department that has been asked by the State Legislature to consider eliminating itself, that is. Funny how that worked out, no? So is this much ado about nothing? Who really cares anyway? Well, I do and here’s why I think you should too:

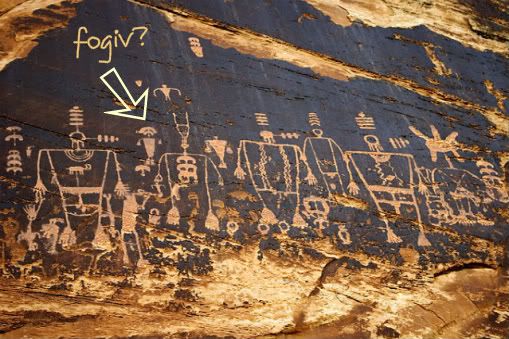

The context and constituents of archaeological sites are ultimately a finite and non-renewable resource that are, in many cases, highly fragile and vulnerable to damage and destruction. Appropriate management is essential to ensure that sites with rich data potential are protected because they can contain irreplaceable information about our past, and the potential to inform both our present and our future. They are part of our sense of national identity and are valuable for their own sake, as well as their role in education, recreation, tourism, etc. Perhaps most important, archaeological sites may represent deeply meaningful cultural ties to a past that would otherwise be lost. There are some things that should not be forgotten. For example:

Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar today announced that the National Park Service is awarding 24 grants totaling $2.9 million to preserve and interpret sites where Japanese Americans were confined during World War II.

“The internment of Japanese Americans during World War II is an unfortunate part of the story of our nation’s journey, but it is a part that needs to be told,” Salazar said. “As Winston Churchill noted, ‘Those that fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it.’ If we are to live up to the ideals expressed in the Constitution, we must learn not only from the glorious moments of our nation’s history but also from the inglorious moments.”

“These places, where more than 110,000 Japanese Americans were unjustly held, testify to the alarming fragility of our constitutional rights in the face of prejudice and fear,” said National Park Service Director Jonathan B. Jarvis. “The National Park Service is honored to help preserve these sites and tell their stories, and thus prevent our nation from forgetting a shameful episode in its past.”

Lastly, significant archaeological sites and other important heritage resources are often relevant to the understanding and amelioration of modern problems. Though archaeologists like me have commonly been associated with efforts to uncover cultural identity, restore the past of underrepresented peoples, and preserve important archaeological/historical sites, our skills and knowledge can be applied in a variety of ways. The art and science of Archaeology has helped city planners in reducing landfills, aided indigenous farmers increase crop yields, guided local communities in tourism development, and helped improve water and other natural resource management. I don’t know what the future holds for the application of archaeology in Utah, but before long we may not know what the past holds either.

24 comments