Padden Creek at Fairhaven Park

Among the icons associated with the Pacific Northwest are evergreen trees, rain, streams, and salmon. These PNW icons have existed in symbiotic relations with one another for probably millions of years. A change in one can affect the others. But apparently this fact was unknown or at least unappreciated by the early American settlers of this region. They over-logged the trees which allowed the abundant rain to wash mud and whole hillsides into the streams which became uninhabitable for the salmon that had used these streams for eons to maintain their life cycles. They also dammed up spawning rivers to provide electricity to run their sawmills and salmon canneries. The irony is that they destroyed the very things that made them wealthy.

The salmon’s life cycle not only sustained the settlers until they degraded it, but also was the primary source food of indigenous populations to whom they were sacred. Further, salmon were critical to the very environment itself as they were an integral component of the larger ecosystem. As they returned to their native streams, they became food for bears and eagles. After spawning, their decayed bodies provided nutrients for the stream’s adjacent riparian flora that protected it.

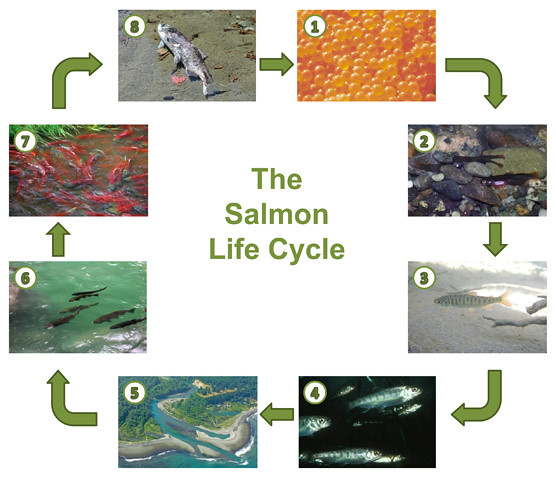

The salmon life cycle is illustrated in this video and outlined below.They begin as eggs and hatch into fry, and grow to smolts. They begin maturation in the streams, lakes or in an estuary until ready to migrate out into the ocean. In the ocean they feed, mature, and grow for two to five or more years depending on species. At their appointed time they migrate to their home creek or river where they go through physiological and morphological changes that prepare them to live in freshwater and spawn. (The homing instinct and directionality are probably magnetically based while finding their birth stream is probably a chemically based sense of smell. This is a fascinating story in itself and not fully understood.) The female enters her stream, and heads up against the current against huge odds until she finds a suitable spot where she clears a 6 to 10 foot by 6 foot space in the stream bed with her tail. This nest-like area is called a redd where she deposits her eggs. Meanwhile the male will protect the area from intruders and fertilize the eggs. The pair may do this several times over a couple of days. The female lays between two and 10 thousand eggs that will hatch in 50 to 150 days. Out of every 1,000 eggs laid, only about one survives to return to the home stream for the spawn.

1. Salmon eggs, 2. Alevins, 3. Coho fry, 4. Smolts, 5. The Elwha River draining into the Strait of Juan de Fuca, 6. Coho migrating to spawn, 7. Sockeye spawning, 8. Dead salmon after spawning.

Salmon habitat degradation began with the early white settlers and continues to this day although thanks to many ecology and conservation conscious groups, including the EPA, various State agencies, Native American Tribes, cities and local non-profit organizations, many long degraded streams are being restored and many with great success.

A major example of one attempt to remedy a large scale salmon habitat degradation is occurring on the Olympic Peninsula within the Olympic National Park where the Elwha River was dammed for over 100 years for electricity that is no longer needed. One dam came down last year and the habitat is rapidly restoring itself. A second dam is scheduled to come down next year. A large stretch of the Elwha is now again running free and river bed and the riparian zones are being reclaimed by nature, inviting the salmon back home.

On a much smaller scale, hundreds of rivers and streams throughout the region have suffered and continue to suffer similar fates, but there might now be hope for significant reclamation. One such stream is in my backyard, actually about 10 blocks to the south. This is Padden Creek in Bellingham WA.

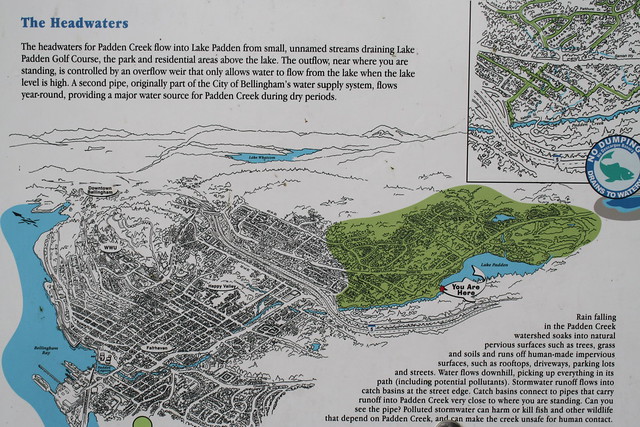

Padden Creek drains in part from Lake Padden and now runs about 2.7 miles before flowing into Bellingham Bay. Before being tampered with it ran 5 miles. The entire creek is within the Bellingham city limits. It also drains about 6 square miles of watershed beginning at the north end of Chuckanut Mountain. On its short journey, it runs through forest, residential, commercial, and farming areas, under Interstate 5, and along and under SR 11. It runs through culverts that direct it under several side streets, by a city park, and along jogging and riding pathways. Finally it reaches its estuary from which it discharges into Bellingham Bay.

Lake Padden

Padden Creek flows here from Lake Paden

Headwaters of Padden Creek

So here begins this little salmon spawning stream as it rolls though, by, and under forest, streets, bridges, culverts, fish ladders, freeways, apartments, houses, businesses, and parks. Finally it empties into the Padden Creek estuary and flows under a train trestle into Bellingham Bay.

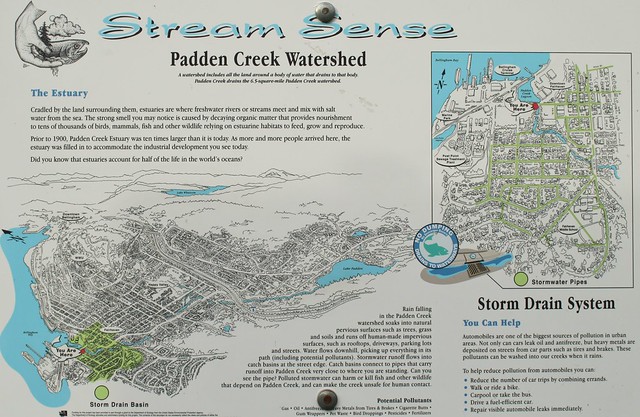

Padden Creek through the 24th St. culvert

The Padden Creek estuary where fresh water meets salt water is vastly changed from before industry settled in the area. According to a sign at the estuary, it was once 10 times its present size. When the tide is out the estuary is now essentially a mud flat with a stream running through it. (See photos below.) However, just outside this estuary are large eel grass meadows full of all sorts of near-shore sea life.These lush meadows provide nourishment for the growing smolts before their journey to the sea. Prior to the coming of industry and the railroad, this was a large, productive estuary that nurtured many young salmon. You might note on the sign the astounding fact that estuaries contain half of the life in oceans.

Padden Creek flows into the estuary under the Harris St. Bridge

Sign post where Padden Creek enters the estuary

The estuary shown from Harris St. Bridge toward train tracks

Looking back to creek entrance and urban encroachment

Looking toward train trestle under which estuary flows into Bellingham Bay

The estuary at low tide is a stream through a mud flat – Notice old wood pilings in mud bed

Eel grass meadow just outside the tracks that serves as part of the estuary

(For those who read my diaries on the fossils of the Chuckanut Formation,

the rocks with green vegetation are part of the Chuckanut Formation)

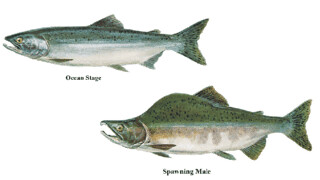

The primary salmonids that have frequented this stream for spawning and nurturing the young are Coho (Oncorhynchus kisutch) aka, silver salmon, and Chum (Oncorhynchus keta) aka dog salmon or keta salmon. Some Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) aka King salmon have been known to frequent this creek as well. These salmon are anadromous, adapting physically to live in both salt and fresh water. Pacific Salmon are semelparous (die after spawning). Two other salmonids found in Padden Creek are species of trout: the Steelhead (Oncorhynchus mykiss) or Seagoing rainbow and searun cutthroat, (Oncorhynchus clarkii ).

Oncorhynchus is a genus of fish in the family Salmonidae; it contains the Pacific salmons and Pacific trouts. The name of the genus is derived from the Greek onkos (“hook”) and rynchos (“nose”), in reference to the hooked jaws of males in the mating season (the “kype”).

Adult ocean phase and spawning phase pink salmon (male)

Padden Creek’s problems began soon after the white settlers arrived and founded the town of Fairhaven (now part of Bellingham) in the 1880s. The area grew quickly with forest and marine industry of fishing/canning, and cutting and shipping logs. Among the usual encroachments of building and industry, the railroad wanted to build a spur where the pesky creek was. Progress is progress, so in 1892, the railroad put in a 2,200 foot long brick tunnel under streets to accommodate the salmon and save the fish. This long straight tunnel replaced and shortened a meandering stream. Even though they thought they were going to save the fish, this tunnel began the demise of their spawning grounds. The tunnel was too long and caused the water to run too fast for the salmon to traverse. There were no quiet pools in the tunnel where the fish could get out of the rapid stream and rest as they made their way to their ancestral spawning grounds. Perhaps with intent to help the salmon, they actually destroyed major parts of salmon habitat. It was rare that any salmon got through the tunnel. Salmon still use the lower part of the stream for spawning, although over half of their ancestral spawning grounds are gone. In some good years the lower stream can still be seen to teem with salmon as their bodies prepare for spawning.

Now for some good news. Starting in 1997, the Padden Creek Alliance began to restore the creek. This alliance includes the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, local community and citizens’ groups such as the Nooksack Salmon Enhancement Association and later the Department of Transportation and the City of Bellingham. This alliance thus far has built a fish ladder and restored the riparian zone along the creek by replanting native vegetation and moving walking paths back away from the creek.

Fish ladder built by Padden Creek Alliance in lower creek

Replanted riparian zone along Padden Creek

One of the final pieces of the restoration is now underway as the State Department of Transportation is constructing a new bridge on State Route 11 that will allow the creek to flow freely in daylight when the city frees the stream from the 124 year old tunnel. This new stream bed will allow the salmonids to swim once again the full length of the creek and up its tributaries.

Construction on new bridge over Padden Creek to replace tunnel

This project will be completed in the next few months, but the salmon’s problem are not yet over. The largest pollutants of the stream come from automobiles and runoff from residential and industrial lands. As noted, this creek runs along and under highways, through residential and commercial areas.

The coming of climate change will also affect the salmon’s life cycle. As both stream and ocean temperature change, so will the food sources of the salmon at sea. Further, the cues that trigger their instinct to return to their streams to spawn may also be affected. If climate change is slow enough perhaps these wondrous creatures might be able to adapt and survive.

Global warming and climate change will soon cause warmer temperatures resulting in more precipitation falling as rain than as snow thus diminishing snowpacks and altering with the timing of stream flows. As more rain than snow occurs, there will be an increase in river flows, as there will be more water released from previously ice and/or snowpacks. This increase in temperature will also cause water temperature to rise overall. Not all of these anticipated effects are necessarily detrimental to the habitat of pacific salmon but they do have severe implications on the salmon population. However, as global temperature increases there will be a higher frequency of severe floods which will result in increased egg mortality since salmon eggs are laid in the gravel at the bottom of streams/lakes/oceans and disturbance of the stream bed will kill the salmon eggs.[7] This flooding will also greatly disrupt the cycles for fall and winter spawning because Pacific salmon spend 2-3 years feeding in the North Pacific and then migrate to their home lake-stream system where they spawn and die.

After years of degrading salmon habitat, we are finally coming around to repair some of the damage on the local level. At the same time, also in the name of progress and economic growth, we are now starting to destroy it at a global level. If this continues, there is little that can be done to fix local streams.

Some possible good news is that in the recent election, we voted in a County Council majority that will likely vote against a major coal port being built in our backyards. In this case, the big coal money was unable to swing the election to the right leaning candidates who strongly supported the coal terminal by dangling non-existent jobs before the electorate. Perhaps there is room for a little hope for us and the salmon.

Here is another part of what we want to preserve:

Great Blue Heron fishing at the Padden Creek estuary

9 comments