My maternal grandfather (1889-1966) was a racist. You won’t read that in his obituary, of course; they only talked about his “noted and controversial” legal career and the fact that he was a Big Cheese in the Roman Catholic laity, honored by two popes. I have the actual cutting from The Houston Chronicle in front of me, still in good condition, so I know there is no mention of his activities with the John Birch Society, his clandestine support of the KKK, or his nightly dinner table diatribes about “those Colored people.” I’m sure he thought his three daughters were thoroughly and safely indoctrinated.

One of those daughters, my mother, went to Rice Institute at the age of fifteen and fell in love with an engineering student from Colorado. Daddy was also the liberal son of liberal, activist parents, and by the time they were married, they were making monthly contributions to the NAACP.

My earliest memories of the Civil Rights protests are not bad ones. When I pulled my head out of my childhood ass and asked questions about what I was seeing on TV, my parents reassured me. They were part-time activists in Texas, fighting to get the hated Poll Tax revoked, registering voters, and monitoring what went on at the polls for the League of Women Voters. “Don’t worry about it,” they told me. “We’re going to make sure things change.” I was proud of them, and proud of the accomplishments of JFK and LBJ.

In January, 1977, I adopted a beautiful baby boy. He was a biracial infant (literally Black Irish) and I was a single white woman. The only thing considered remarkable about the adoption was the fact that this was the first time a single parent was allowed to adopt a baby in Harris County, TX. When someone asked me if I worried about racism I, in a moment of appalling ignorance, said no. “It’s just a matter of time,” I said. “We got the laws changed; hearts and minds will follow.”

Well. Of course it wasn’t long before the crap started. My co-workers decided there was no need to have a baby shower for “that” baby. I ended up buying a gun when I received anonymous threats on his life. Certain white people would see me with him in stores and I could tell their minds made the jump from a pretty brown baby to the mother in bed with a Black man. I later learned that my oldest friend, who often went with me to the grocery store, would sometimes follow those staring, judgmental racists and, when I was out of sight, demand, “Just what the hell do you think you’re staring at?!”

Fortunately, everyone who took the time to get to know Michael fell in love with him. Certain family members who had been using the N-word behind closed doors began calling and asking me to bring him to their homes. I kept him in the same racially diverse neighborhood for most of his childhood, attending schools with children of many racial and cultural backgrounds. Not all hearts and minds may have changed, but we chose to live our lives with people who saw sweetness, not color.

My son grew up, got his degree, and married his college sweetheart, a young woman whose parents came from the Philippines. Their bloodlines produced a breathtakingly beautiful son six years ago, and they continue to live productive lives in their community in North Texas.

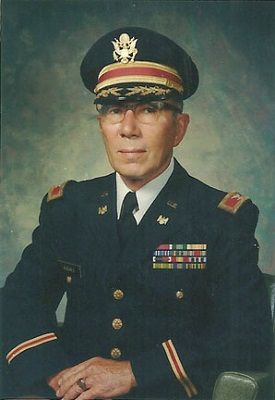

That photo, taken last Christmas, doesn’t include the most recent addition to our family. A second son was born in June: